Why policymakers must take action

Global construction is centred in cities. By 2050, an additional 2.5 billion people are projected to live in cities, and as urban populations grows, the need for new buildings and infrastructure will intensify. Cities have a growing responsibility to mitigate construction’s role in the climate crisis.

Cities are uniquely positioned to promote and support the transition from a linear to circular economy, particularly in construction and urban development. While some cities have already taken up the challenge to start working with circular economy principles to minimise their impacts, an understanding of how to holistically implement circular solutions often remains blurry.

The CIRCuIT project developed specific lessons related to circular construction in cities – such as Transformation (Chapter 1), Urban mining (Chapter 2) and Design for Disassembly and Adaptability (Chapter 3) approaches. Now these learnings need to be translated into clear recommendations for action.

Two significant areas of influence for cities are through their planning and procurement policies. For example, by leveraging procurement power, cities can set the level of ambition for the entire city providing a strong signal of confidence for the sector or specific solutions. Cities can also use procurement requirements to bolster their own climate priorities, targets and strategies through clauses that address embodied carbon or city regeneration, among others.

Embedding circular strategies into planning policies helps to scale up action and introduces a much larger portion of the supply chain to circular solutions. However, all policy changes need to be supported by open dialogue, a factor that CIRCuIT explored through developing a dialogue tool.

This chapter outlines a range of different policy mechanisms to drive circular construction, a dialogue tool to guide productive conversations between developers and cities and illustrates the roadmaps CIRCuIT cities developed to put these into actions.

While some cities have already taken up the challenge to start working with circular economy principles to minimise their impacts, an understanding of how to holistically implement circular solutions often remains blurry.

Barriers to circular action in cities

The CIRCuIT project identified specific barriers to circular action in cities that city decision makers must consider when outlining their change making mechanisms. Addressing these barriers can help policy makers design effective interventions.

Regulatory barriers: Failure of a policy to be clearly defined, aligned and/or enforced across national, municipal and local hierarchies. When these various layers do not enforce each other (or contradict each other) this can lead to confusion. Regulatory barriers can also include overreach of regulations, like energy efficiency, that inadvertently make circular solutions more difficult.

Market barriers: Failure of the market based on communication and access. This can happen when there isn’t a common language to define needs (for example missing standards and data). Businesses can have trouble accessing the market due to missing or unaligned standards as well as lack of communal infrastructure needed to support the market – for example material storage and exchange depots.

Economic barriers: The current financial system values new materials and conventional construction far above circular approaches. In some regions, such as the UK, retrofits are taxed at a higher rate than new construction. This means it is often financially impractical to pursue circular construction as incentives are not currently provided for circular economy approaches. Where incentives are available, they are not divided equitably along the supply chain to further drive circular construction. Upskilling built environment professionals to enable uptake of new approaches can also be prohibitively expensive.

Process barriers: The conventional construction process can sometimes be a barrier. Barriers can include the large multidisciplinary teams on projects and comparatively low margins on budget. Circular activities that prolong the construction period are unlikely to be successful – they cost the investor more both in terms of running the construction site and ‘missed’ rent while the building isn’t operational.

Social barriers: Uptake of circular construction practices requires behavioural change. Lack of knowledge, interest or awareness of construction techniques can stall progress, as can the perception that any change is inevitably more expensive. In addition, construction does not have a collaborative culture people can harness to easily break through these cultural barriers.

Circular activities that prolong the construction period are unlikely to be successful – they cost the investor more both in terms of running the construction site and ‘missed’ rent while the building isn’t operational.

Embedding urban development policies

City administrations can harness a range of policy interventions to further circular action and overcome barriers to circularity. Adopting new circularity-related regulations can require significant changes both in terms of process and cultural expectations. Transitioning towards a circular approach to construction means changing what and where cities build, how spaces are developed and how materials are made, recycled and used.

Policies can be adjusted to align with local stakeholders’ capabilities and the varying levels of support from national governments. For example, they can be supported by integrating non-regulatory practices, such as developer dialogue tools (page 5-12), which help develop open circularity conversations between cities and industry.

For the full list of policy interventions, and the specific recommendations for interventions in each of the four CIRCuIT cities, please see 7.1 Circular economy in urban planning at circuit-project.eu/post/latest-circuit-reports-and-publications

Policy recommendations are presented in three key areas of circularity action: transformation and life cycle extension, urban mining and material reuse and design for disassembly and adaptability. They cover five types of policy instruments:

Legislative and regulatory: Policy interventions relating to requirements for planning or demolition, licences and permitting, data reporting and design requirements.

Economic and fiscal: Relating to taxes or levies on certain behaviours, as well as subsidies or investments from the city.

Agreement and incentive-based: Interventions related to collaborative actions and agreements between parties. Can also include pledges, commitments and voluntary certification schemes.

Strategy, roadmap and information-based: Interventions that support direction and knowledge, written roadmaps and guidelines or eco-labelling, widespread use of best practice case studies.

Knowledge and innovation: These tackle more systematic knowledge gaps through upskilling and training, curriculum changes and stakeholder engagement.

Policy interventions to embed circularity in cities

Transition to circular construction requires system change. This means it can be beneficial to implement a range of policy interventions that reinforce each other. For example, if there’s a legal requirement to increase the use of reused and recycled materials (legislative/regulatory instruments) this could be supported by a primary materials tax (economic instrument) and pilots to determine best practice (knowledge/innovation instruments).

Life cycle extension and transformation drivers

Encourage planning authorities to prioritise reuse of assets in strategy and culture – Changing perceptions of the value of existing buildings from strictly cultural to environmental due to the sunk carbon costs in all planning authority operations.

Strategy and roadmaps

Ensure zoning and planning regulations do not restrict refurbishment – Reviewing requirements and removing certain elements (e.g. stringent energy efficiency requirements, densification blockers) that make it harder to maintain existing buildings.

Legislative/ regulatory

Require demolition and rebuild vs. retrofit carbon assessment of site before issuing demolition or new development permit – Assessments can reveal which intervention is more effective from a carbon perspective. Ensure the scope is considered too – emissions saved in the next 10 years are more impactful than those saved in 60 years.

Legislative/ regulatory

Urban mining drivers

Require a minimum time between demolition permitting and demolition activity – Time is a very valuable resource in construction. Requiring a minimum amount of time between permitting and demolition means reusable and recyclable materials are more likely to find a useful second life. Time delays can also be enforced for projects that choose to demolish rather than deconstruct and reuse materials so there is no time benefit to conventional, non-circular demolition practices.

Legislative/ regulatory

Require a pre-demolition audit before issuing a demolition permit or approving a new development permit including how waste will be minimised – Pre-demolition audits ensure the material on site is catalogued and assessed for reuse or recyclability. Requiring this step means all projects must consider what to do with the buildings on their existing site.

Legislative/ regulatory

Set requirements (%) for amount of material (waste) reused/recycled in demolition permit – Ensures a baseline level of reusable materials in the city market.

Legislative/ regulatory

Require waste hauler to be licenced and identified in the demolition or new development permit – Ensures material reuse and recycling is traceable and second uses can be verified.

Legislative/ regulatory

Require buildings meeting specific criteria to be deconstructed, not mechanically demolished – Certain building types that include specific desirable building materials (e.g. single family homes built with old growth timber) should be required to be deconstructed carefully to allow for maximum material reuse of high value materials.

Legislative/ regulatory

Make pre-demolition audit information public – Pre-demolition audits are a great source of city-level data on material flows. Making the granular data publicly accessible means better predictions and smoother secondary reuse markets are possible.

Knowledge and innovation

Set requirements (%) for number of reclaimed/recycled materials incorporated in new development permit – Ensures a baseline of secondary material demand to drive the secondary reuse markets.

Legislative/ regulatory

Ban use of certain (non-circular) materials – Helps ensure effective urban mining is possible in the future.

Legislative/ regulatory

Design for disassembly and adaptability drivers

Set requirements that short life span buildings should be modular or prefabricated – If use cases for the building are limited to the short term require modular and demountable structures be considered.

Legislative/ regulatory

Set disassembly targets for shorter lifespan or higher reuse potential buildings or elements.

Legislative/ regulatory

Multiple circularity solution drivers

Articulate clear planning strategy that centres circular and regenerative solutions – Establishing public goals and priorities can help the local supply chain adapt and better meet the near-future needs of the city.

Strategy and roadmaps

Allow larger development areas where certain circularity approaches are applied (e.g. % reused materials, % existing building maintained) – Provide an indirect financial incentive by allowing more square metres of development as reward for exemplary circular practices.

Agreements/ incentive

Provide a ‘fast-lane’ permitting process where certain circularity approaches are applied (e.g. % reused materials, % existing building maintained) – Provide an indirect financial incentive by allowing construction to proceed more quickly as reward for exemplary circular practices.

Agreements/ incentive

Reduce permitting fees where certain environmental criteria are met (e.g. retention of existing building, reuse %, carbon footprint, green building rating scheme) – Provide a direct financial incentive by allowing construction to proceed more quickly as reward for exemplary circular practices.

Agreements/ incentive

Support innovative pilot projects – The city can support exciting new projects in the area, blazing a trail for other circular work.

Economic/fiscal

Train city staff and supply chains – Policy implementation will happen much more smoothly if the people on both sides of the table understand circular construction. The city can support training initiatives, especially for smaller businesses who may not have the resources to develop this knowledge on their own.

Agreements/ incentive

Supporting circular economy policies: In dialogue with developers

Relevant and well-developed policies cannot be created, or enforced appropriately, without the support of the local construction sector. Working to establish an open and supportive communication channel between city officials and developers is key to achieving sustainability and circularity goals. This seven-part check list can support this dialogue.

1. Give developers a vision

Developers say they often feel confused about a city’s direction on the circular economy. This can lead to business-as-usual practices.

To tackle this, cities need to prioritise their circular goals and communicate them clearly to urban planners and developers. They also need to ensure that these goals relate to existing agendas, such as an overarching objective of becoming carbon neutral.

Developing and sharing a circular economy strategy and roadmap for a city’s built environment will also help create a clear vision for developers.

2. Provide a clear overview of the planning process

A city’s planning process can appear complicated. Developers may not know when and how to introduce circular economy initiatives.

A good way a city can help overcome this problem is by visualising all the stages of their planning process. At each stage there should be easy-to-understand information about what is expected from a developer and which city officials will work with them.

It’s important each stage should also clearly explain what a developer can do to help embed circular economy principles in their project.

3. Talk about circularity as early as possible

To increase the probability of circular approaches being adopted, it’s critical city officials speak as early as possible to developers about them.

These conversations must start before demolition of existing structures and a developer submits their planning application.

This can be done by organising sustainability kick-off meetings with developers, consultants and all relevant city officials.

4. Identify common circular interests and goals

A developer may have a different objective or perspective than a city on the circular economy, or they may believe circular objectives and requirements are out of reach.

To increase the chance of circular activities being adopted, cities should work with developers to identify common sustainable interests and goals, such as reusing components from demolished buildings.

City officials should continue to work with and support the developer to ensure that any common objectives are achieved.

5. Discuss incentives for developers to adopt circular practices

Circular construction is not yet a top priority for most developers. To change this, municipalities and developers should agree incentives, which could include:

Developers being exempt from certain regulations if they adopt circular approaches. For example on energy demands, material longevity or documentation requirements.

Developers being allowed to increase the floor area offered by a building if it is constructed in a way that meets specific circular targets.

6. Establish channels for communicating policy change and circular economy knowledge

For a developer to be in a strong position to implement circular economy approaches, it’s important they have a good knowledge of a city’s planning process and circular construction practices.

To do this, a city should establish an official channel, such as an online forum, they can use to communicate planning process changes and knowledge about building sustainably and the circular economy.

A city should also set up an internal network for urban planners and other city officials engaged with the circular economy agenda. The officials could use this network to ensure their planning practices are aligned in a way that increases adoption of circular practices.

7. Use circular economy data and best practice to drive action

Hard evidence and best practice often play a key role in changing behaviour.

Cities should collect data on circular construction initiatives and the environmental, economic and social benefits they deliver. Also, they should create a catalogue of best practice building projects that have used circular economy principles.

Share data and case studies with developers, urban planners and other built environment stakeholders to increase their knowledge and encourage similar action.

If a city is unsure how best to do this, or generally lacks knowledge about the circular economy, it should consider hiring a circular construction expert to support city officials and local developers.

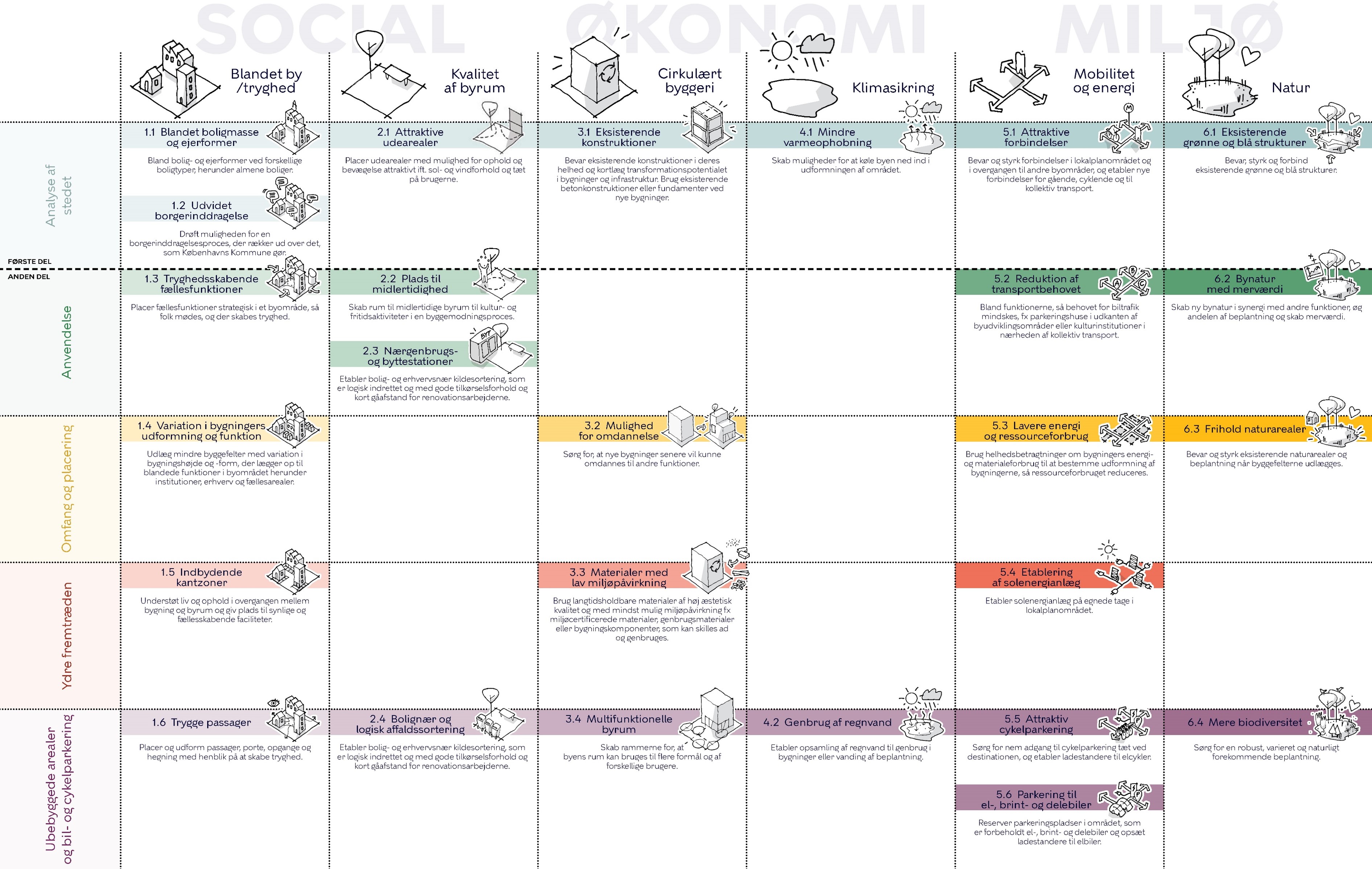

The Copenhagen Sustainability Tool (CST) in action

A Copenhagen Sustainability Tool (CST) was developed to improve dialogue on sustainability between the planner and developer. The CST is a discussion tool that helps the city planner effectively communicate the city’s strategies on environmental, social and economic sustainability and options for the developer to support these priorities. The planner, developer and consultants use the tool to choose 3-5 of the most relevant initiatives and assess how to integrate them into the final development plan. This plan is then submitted to the city council including outcomes of the dialogue. The tool will be updated to focus on CO2 reduction and material reuse and recycling as key initiatives for dialogue.

Embedding circularity: Using public procurement

Incorporating circular economy principles into public procurement has potential for large-scale positive impact. In Europe, public procurement accounts for approximately 14% of GDP. This means the demolition, renovation and construction of a city’s own buildings are a great opportunity to lead by example, promote, trial and normalise circular construction.

Current procurement practices are generally optimised to minimise short-term financial cost. This doesn’t capture the long-term financial and environmental benefits circular practices can deliver. Circular economy solutions are innovative – and municipalities must adapt and incorporate new developments into procurement practices. Even in cases when sustainability and circularity goals are named priorities, there can be issues seeing requirements carried through to the final product.

This is for a few reasons:

When circular economy criteria are outlined in public sector tenders, they tend to feature ‘soft’ wording (like ‘striving for’ sustainability) rather than hard targets. There are no consequences for missing these targets.

Without defined circularity targets to hit, there can be different interpretations of what a circular approach looks like. This makes it difficult for a city to assess proposals and identify the best one for a project.

Existing sustainability construction standards, such as DGNB or BREEAM, are sometimes used in public procurement tenders to encourage sustainable and circular economy practices. However, not all the criteria in these standards are prioritised and enforced to the same extent. Circularity criteria is often less prominent, leading to mixed circular outcomes for a project.

To help city governments overcome these issues, CIRCuIT partners developed a set of circular economy criteria that any city can include in their tenders for public demolition, renovation and construction projects. When applying this criteria cities should consider these points:

Procurement criteria is most effective when formulated as minimum requirements in the tender document, rather than as award criteria, to ensure implementation in a project. This way circular economy strategies will be incorporated in all bidders’ proposals while price, quality and additional sustainability factors will remain the competitive elements of the bid.

The highest priorities should be maintenance, repair, refurbishment, renovation and transformation of buildings to achieve circular economy. This means procurement criteria should place more emphasis on them.

Municipalities should select criteria relevant to the stage of the project. Some criteria will be useful in tenders for a concept development, while others will be useful for execution of a demolition project.

For the full list of criteria and a complete discussion of the procurement work please see D7.4 Recommendations: Criteria for public tenders on construction at circuit-project.eu/post/latest-circuit-reports-and-publications

Recommended circular economy criteria for public sector tenders

Recommended circular economy criteria for public sector tenders

Renovation

Avoiding demolition through investigating transformation opportunities can extend the life of the building, and promote life cycle value creation. It also reduces resource use and the developers’ carbon footprint while potentially safe guarding the cultural value of existing buildings.

Require a screening of potential new use in the transformation –-This requires study of each building in terms of condition, location, local plan and spatial structure. Design of different transformation scenarios and recommendations for project to select should be provided.

Project development stage

Require a feasibility study of vertical extension potential in renovation projects –- The vertical extensions can be used to meet carbon footprint targets. This requires a study of each building for condition, location, local plan and spatial structure.

Design stage

Require LCA and LCC calculations for comparison of different renovation and transformation scenarios Decisions on which renovation or transformation strategy should be chosen should always consider the potential savings on carbon footprint. Some CO2 -limits may be set by legislation or by the city. LCA and LCC calculations and their comparison should be required for different scenarios to make an informed decision for project execution. A light version of LCA and LCC can be required in the design stage of the project. The in-depth LCA and LCC can be required before the execution stage.

Design stage Execution (construction) stage

Demolition

Requiring circular economy criteria for the demolition stage can help reduce demolition waste by extending the life cycle of existing materials. This can inturn reduce natural resource use and energy consumption, due to no virgin material excavation and processing.

Require a pre-demolition audit – Require the timeframe of the audit and a list of stakeholders participating. Ensure you provide a template to allow for comparable and detailed reporting.

Execution (demolition) stage

Require training certification from demolition personnel – Require reference to specific training for demolition personnel.

Execution (demolition) stage

Require a plan for storage of recovered elements –- Require a plan on-site or off-site for recovered material before demolition starts. Preferably on-site storage to prevent transportation.

Execution (demolition) stage

Require a plan for material reuse –-Require assessment of potential reuse of material after recovery. Ideally, this should happen before demolition to prevent long-term storage and transportation.

Execution (demolition) stage

Construction

Requiring circular economy criteria for the construction phase can help future proof buildings requiring considerations for future reusability and adaptability. In the next iterations of the building this can reduce on site waste creation and reduces the need for new materials by supporting reuse.

Require a plan for potential future uses of the project Ask project teams to outline potential future uses for the project – this can be a change of use for the building, future retrofit or building relocation.

Project development stage Design stage

Require an outline of estimated life span for each building layerAsk project teams to estimate the life span of different building layers (structure, façade, building services, space and stuff).

Design stage

Require a DfA and DfD approach for each building layer based on potential future uses and lifespan Ask project teams to outline what DfA and DfD can be applied to each building layer based on potential future use and the expected life span.

Design stage

Require a LCA of DfD and DfA strategies and their potential impact on cost and carbonAsk the project team to conduct a LCA on at least three DfD and DfA strategies applied and realised to different building layers and compare against not applying it.

Design stage

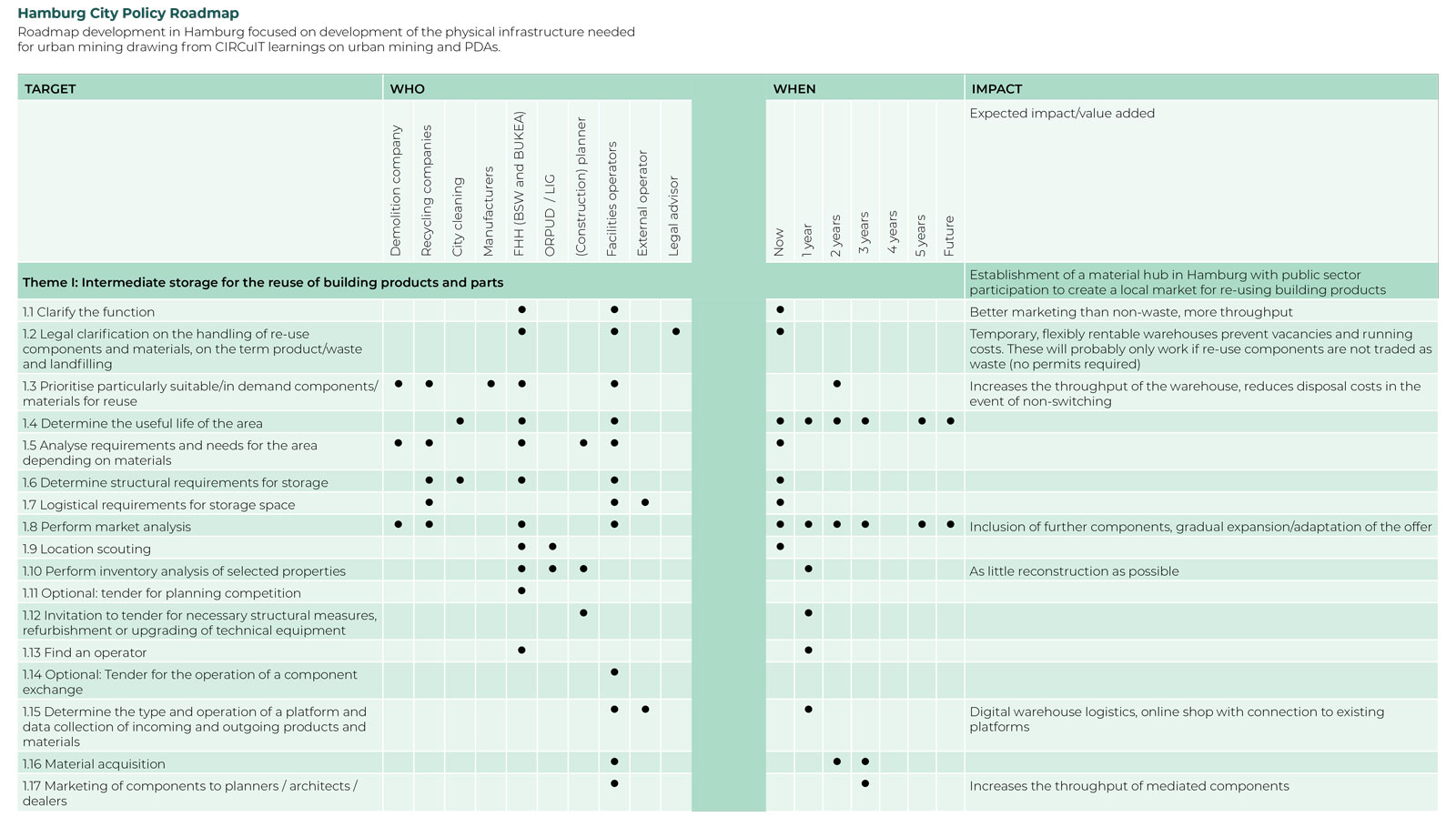

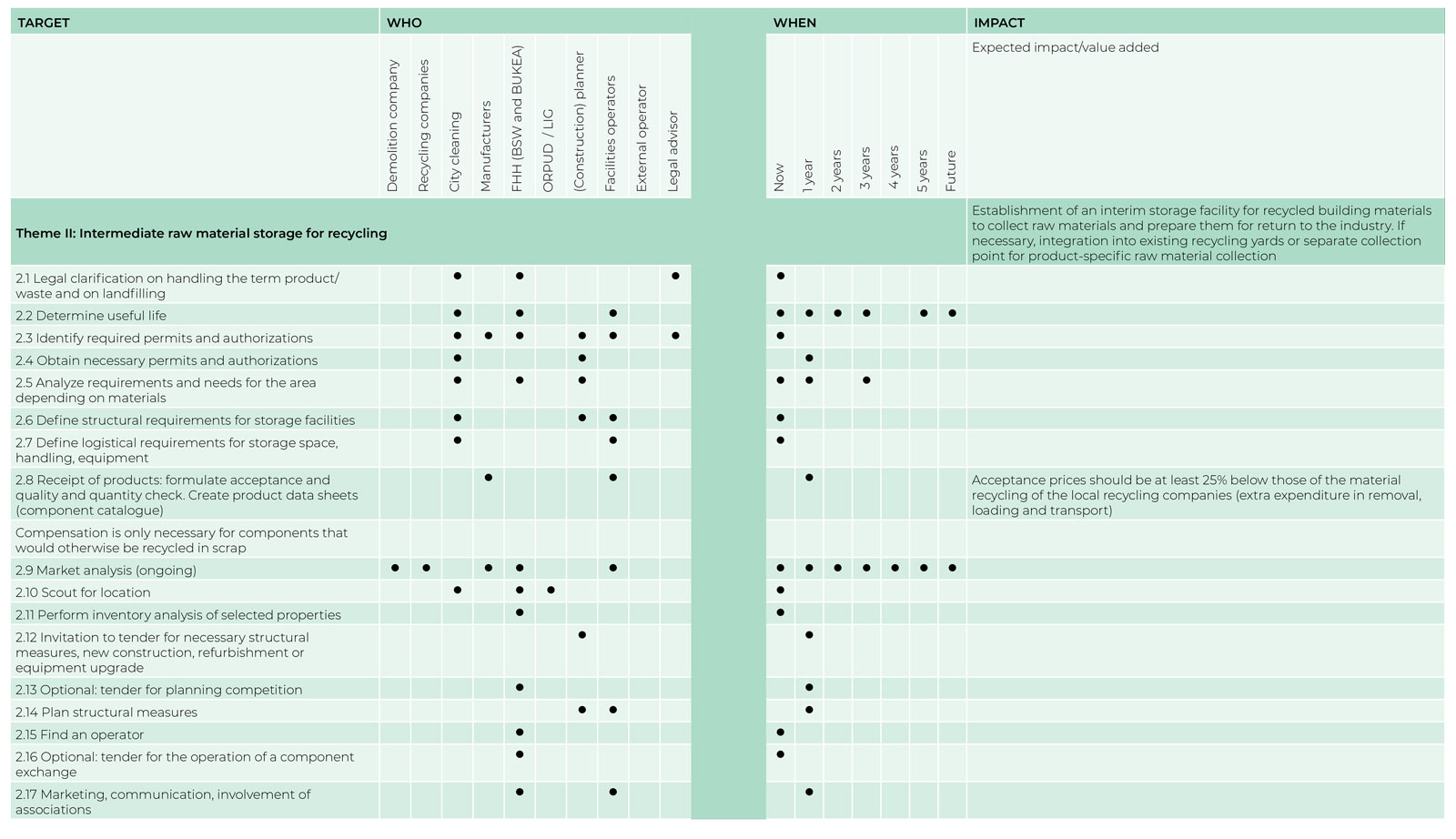

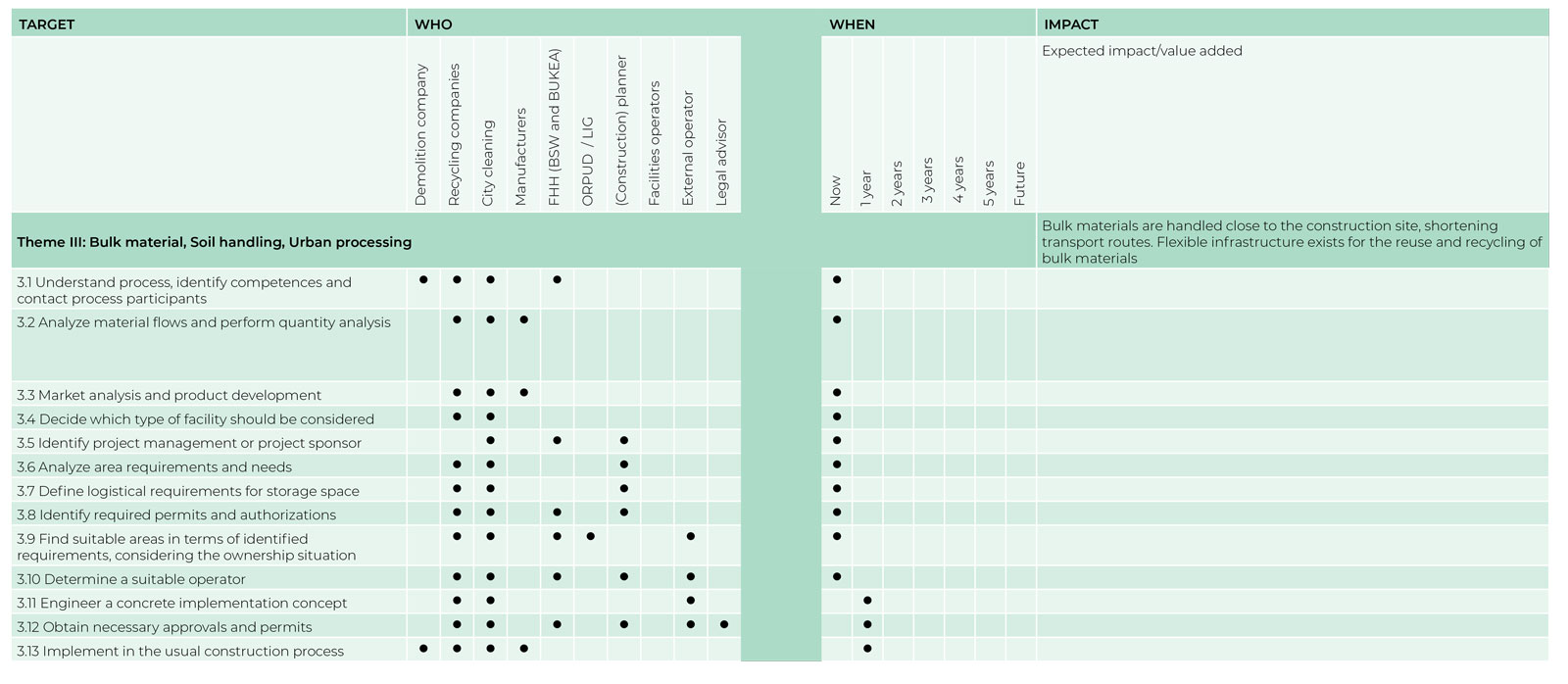

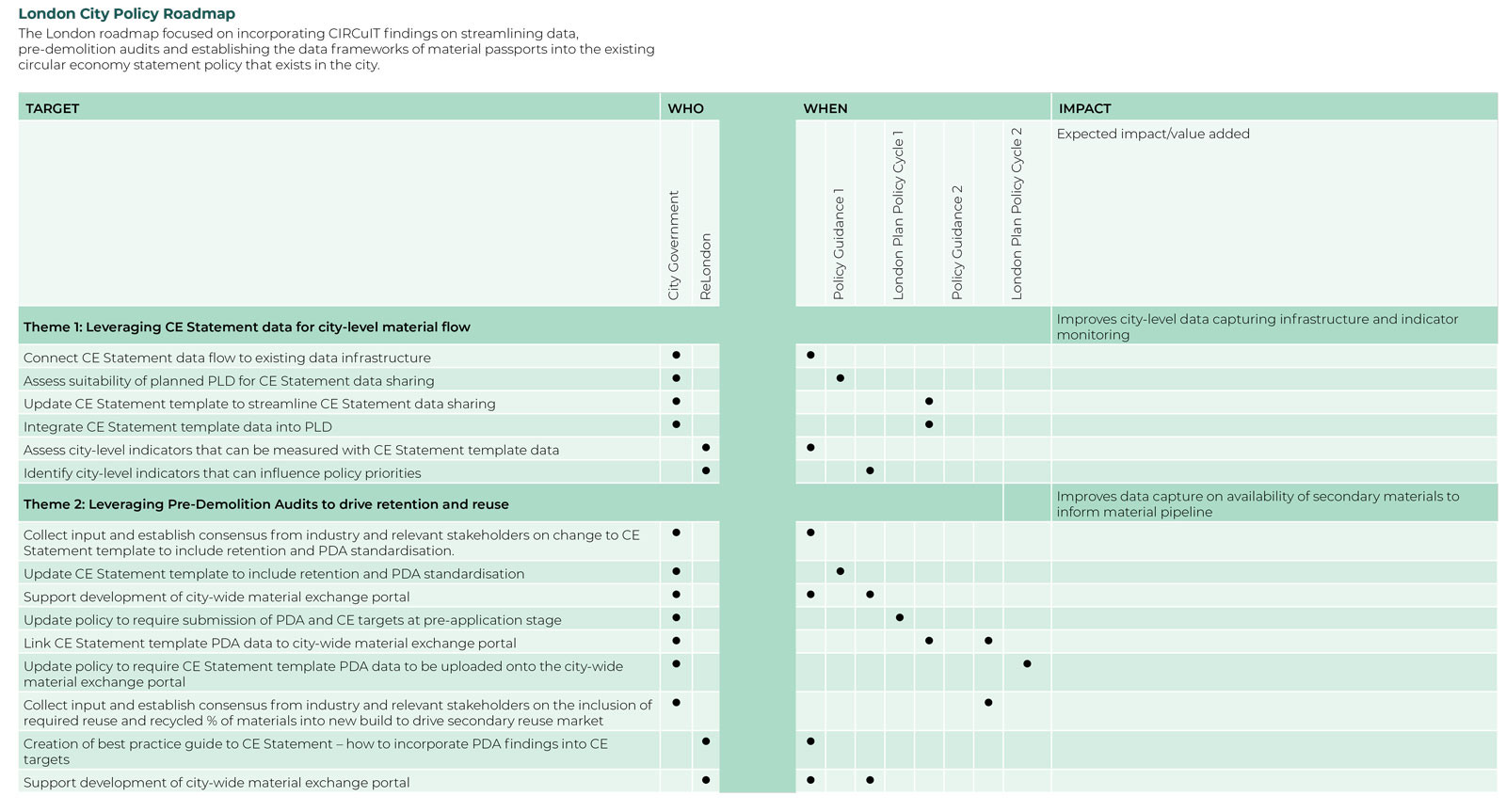

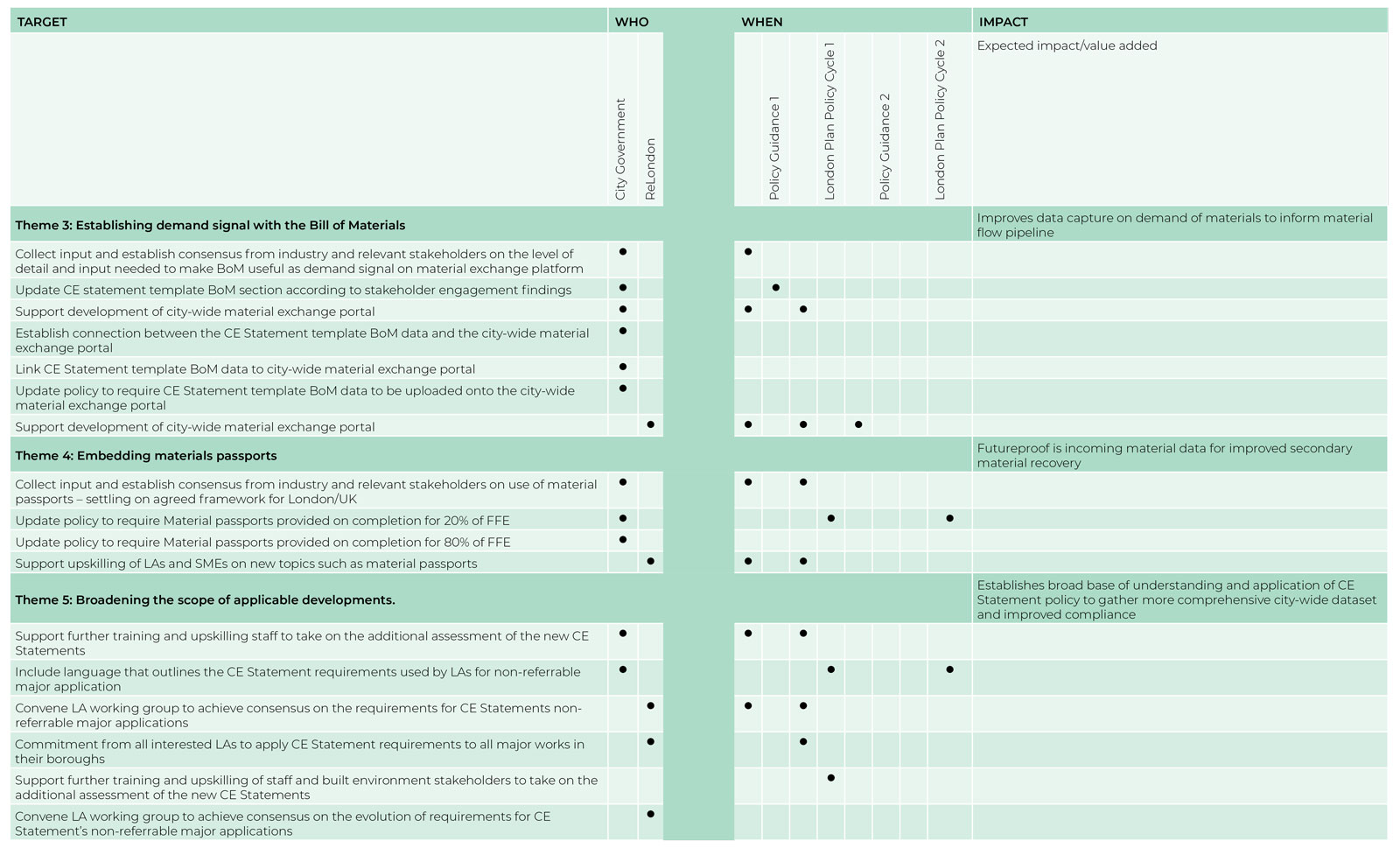

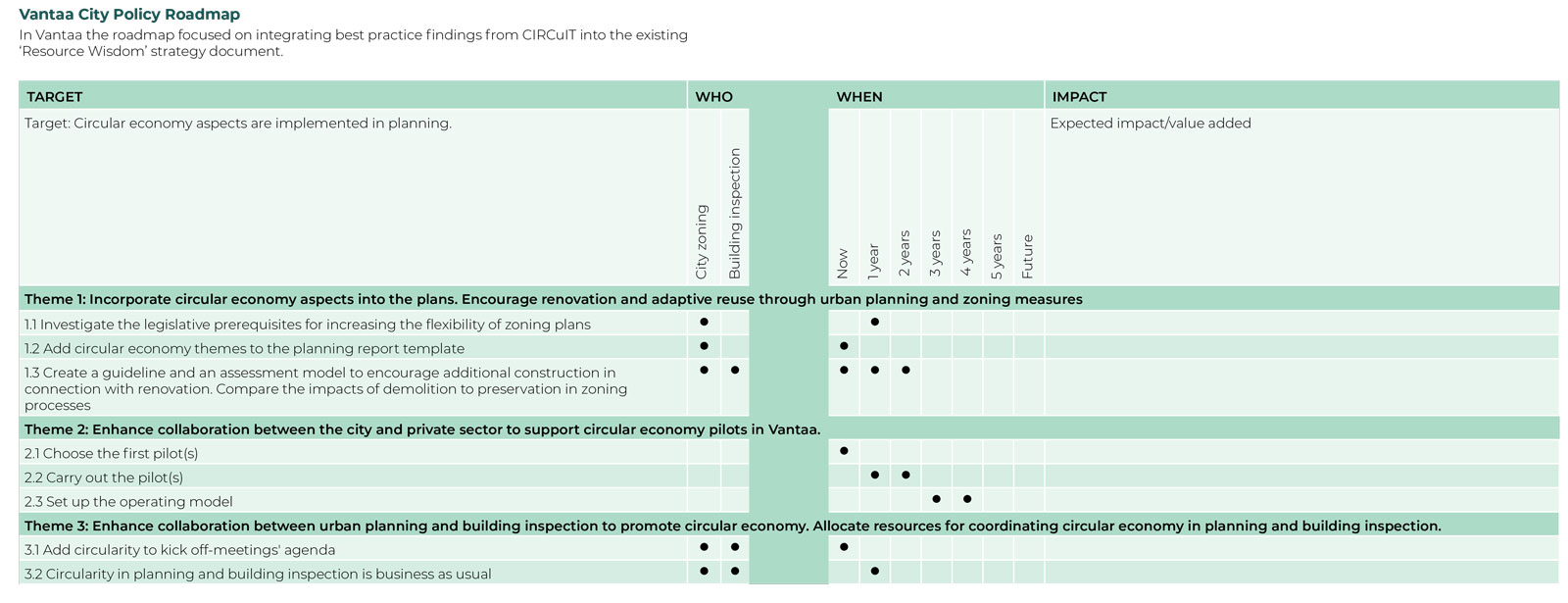

How to embed policy best practice in policies and practices: City Policy Roadmaps

Despite cities embracing the task of incorporating circular economy principles, the sequence of implementation and integration into existing workflows can remain tricky. The four CIRCuIT cities each reviewed the wide range of circular recommendations developed by the project and considered these alongside their city’s needs, environmental priorities and ambition. The result is four circularity strategy roadmaps all developed from a different and unique perspective. The sequence of actions and pace of change can support similar action in other cities where the context may be similar.

For the full roadmap descriptions see D7.6 Implementation of Circular approaches into city planning at circuit-project.eu/post/latest-circuit-reports-and-publications

Further reading

Further reading

For further information about these outputs and the work behind them, please read the following reports, which were published by members of CIRCuIT partner organisations during the lifetime of the project.

D7.1 Circular economy in urban planning and building permits – possibilities and limitations

D7.3 Recommendations: Instruments for the dialogues with developers

D7.4 Recommendations: Criteria for public tenders on construction

D7.5 How to implement the EU guideline for pre-demolition audits

D7.6 Implementation of Circular approaches into city planning

All these reports can be downloaded at circuit-project.eu/post/latest-circuit-reports-and-publications

Acknowledgements

The following individuals authored the deliverables that form the basis of this chapter.

Ann Bertholdt, The City of Copenhagen

Annette Schröder, Eggers Tiefbau

Ariana Morales Rapallo, Hamburg University of Technology

Colin Rose, ReLondon

Elina Mattero-Meronen, Helsinki Region Environmental Services Authority

Frank Beister, Otto Wulff

Henna Teerihalme, Helsinki Region Environmental Services Authority

Janus zum Brock, Hamburg University of Technology

Justyna Bekier, The City of Copenhagen

Karolina Bäckman, GXN

Kimmo Nekkula, The City of Vantaa

Mahsa Doostdar, Hamburg University of Technology

Mathias Peitersen, The City of Copenhagen

Philipp Wendt, The City of Hamburg

Pia Kohrs, The City of Hamburg

Rachel Singer, ReLondon

Rune Andersen, Technical University of Denmark

Silke Bainbridge-Nott, Otto Wulff

Simon Gühlstorf, Otto Dörner

Tessa Devreese, ReLondon

Tiina Haaspuro, Helsinki Region Environmental Services Authority

Uta Mense, The City of Hamburg

Image credits

Asger Nørregård Rasmussen, Maker

Gareth Owen Lloyd, Clear Village